The oil and gas industries have just experienced a year of exceptional profits, with shareholders receiving record payouts. In its wake, the European companies Shell and BP I returned on their ambitious plans to transition to a low-carbon economy, with companies in the sector increasing their investments in new production.

This is not good news for climate changelargely powered by burning fossil fuels. One worry is that these investments mean the industry and its political allies will fight tooth and nail to avoid them.blocked assets» losses, blocking higher production of climate change-related fuels for years or even decades to come.

Not only corporations, but also their shareholders could transform themselves, as special interests, into a broad coalition against green energy. In the United States and the United Kingdom at least, most pensions are invested in the capital markets, where in the stock markets oil and gas companies remain among the highest generators of dividends and share buybacks. reliable. All this could dissuade governments from implementing overly ambitious measures. climate change mitigation policies for fear of causing financial losses to a large part of their own voters.

But based on recent analysis, we assert that high-income governments don’t have to worry about triggering these financial losses. Indeed, most of the consequences of stranded fossil fuel assets – lower production volumes or sales at lower prices than investors expected – would fall mainly on the richest members of these countries. This is not the case for most voters.

The explanation is relatively simple: these nations all have significant inequalities who owns the companies. This means that the wealthy generally own the vast majority of all stocks and bonds, and there is no evidence of a significant difference in the oil and gas sector.

Governments should indeed be concerned about the potential effects on fossil fuel users, such as car owners, caused by carbon prices and other climate policies that impose penalties on consumption, and significant Proposals have been made for measures to reduce the negative effects of fossil fuels. phasing out the most vulnerable people in society, such as “carbon dividends » And improved public transport. Governments should also care about the plight of workers in the energy and other sectors and ensure a just transition for communities powered by fossil fuels. However, for financial investments, the poorest 50 percent or even 90 percent of wealth owners could be compensated at a very low cost compared to these other measures.

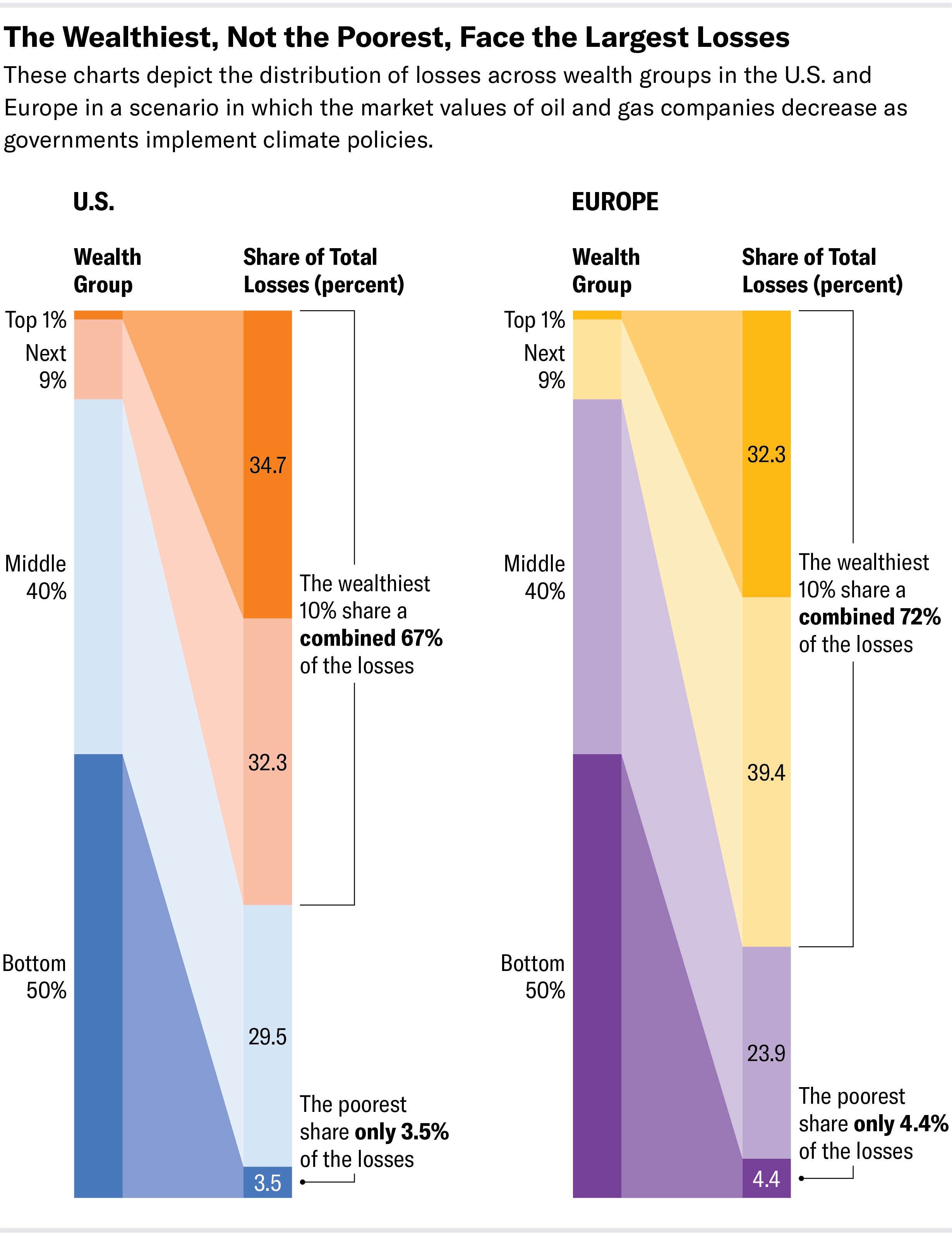

We have previously calculated than in a scenario where oil and gas companies are initially valued based on expected participation in a growing oil and gas market, but governments around the world implement climate policies limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial averages, this could lead to wealth losses of nearly $550 billion for US and European shareholders as company stock values are readjusted to these lower expectations. However, once we analyze the likely place of these shareholders in the wealth distribution, it turns out that only 3.5% in the United States and 4.4% in Europe of losses harm the portfolios of the 50%. of them the poorest (see graph). Simply put, those who own the most stocks also own most of the oil and gas stocks that are being devalued.

However, because the top 1% and top 10% are so wealthy (each American adult in the top 1% has on average more than $13 million in net wealth), these losses, distributed among individuals, barely appear in their portfolio. We estimate that the losses amount to less than half a percent of the net wealth of the richest 1 percent or 10 percent of Americans, for example. Additionally, as fossil fuels decline, new investment opportunities emerge in growing markets for low-carbon alternatives that enable portfolio hedging. Even the losses of the bottom 50 and 90 percent do not represent a large percentage of their wealth. The worry might stem from the fact that they have so little wealth in the first place. Compensating the poorest 50% would cost only $12 billion in the United States and $9 billion in Europe, in a $550 billion loss scenario. This could be paid for with just one-sixth of annual revenues from a notional price of $13 per ton of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions, which is well below current consensus estimates of the social cost of carbon. In Europe, this could also be rewarded with around 20% of revenues from the European Emissions Trading System (ETS) in 2022.

It could be argued that the rich are much savvier investors and will exit their investments before stocks lose value, thereby imposing much greater losses on the poor. This is indeed a concern, but our robustness calculations suggest that even if the poor were much more likely to hold oil and gas stocks, compensation costs would still be limited.

There are many barriers to moving away from fossil fuels, from prices for consumers and businesses to jobs and meaning in communities where fossil fuel production is concentrated. Governments must approach all of them carefully. However, losses suffered by financial investors are not part of this, and even if they were, we show that compensation for any socially relevant losses would indeed be cheap.

Warnings about pension losses and resistance to measures that could cause assets to become stranded appear largely in the interests of the very rich, whose capacity to absorb losses is arguably far greater than that of the rest of the population. world. In contrast, losses from unmitigated climate change are likely to hit the poor and vulnerable much harder.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the opinions expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily those of Scientific American.